In March 2019, the New Mexico Museum of Art (NMMoA) reached out to Greater Chaco Coalition and the artists of the art zine Imbalance to request printed copies of the art zine for distribution at the museum in conjunction with the exhibition Social & Sublime: Land, Place, Art.

NMMoA received 1,162 copies of this art zine from artist Asha Canalos for museum programming.

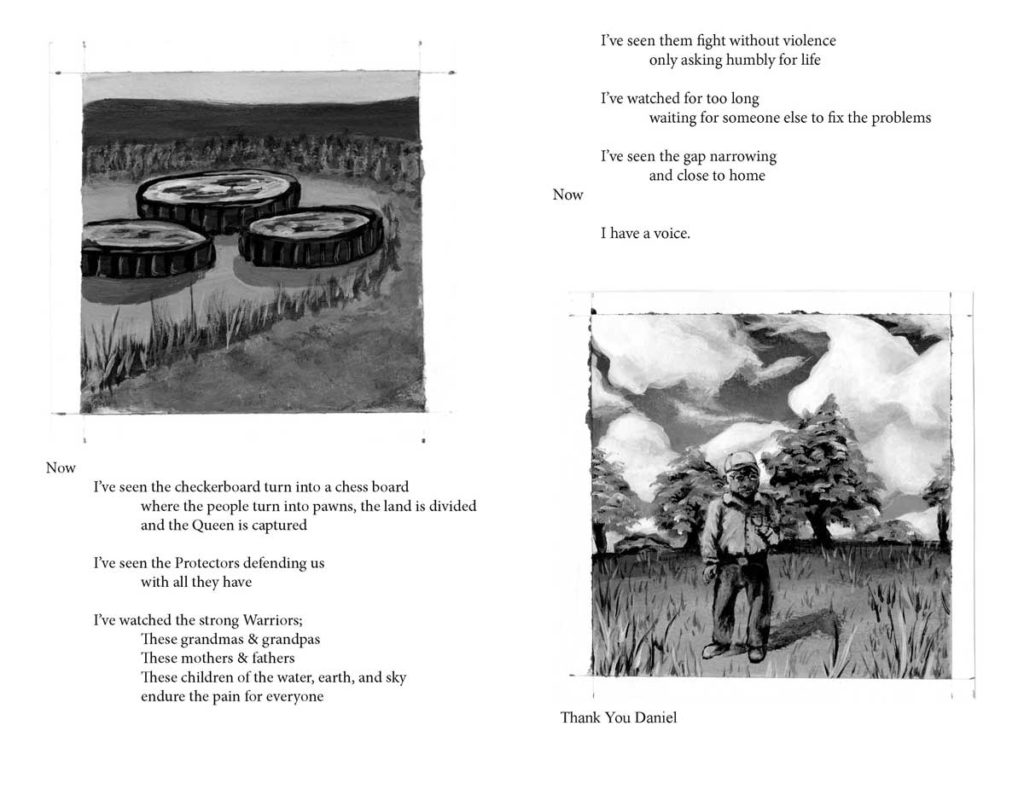

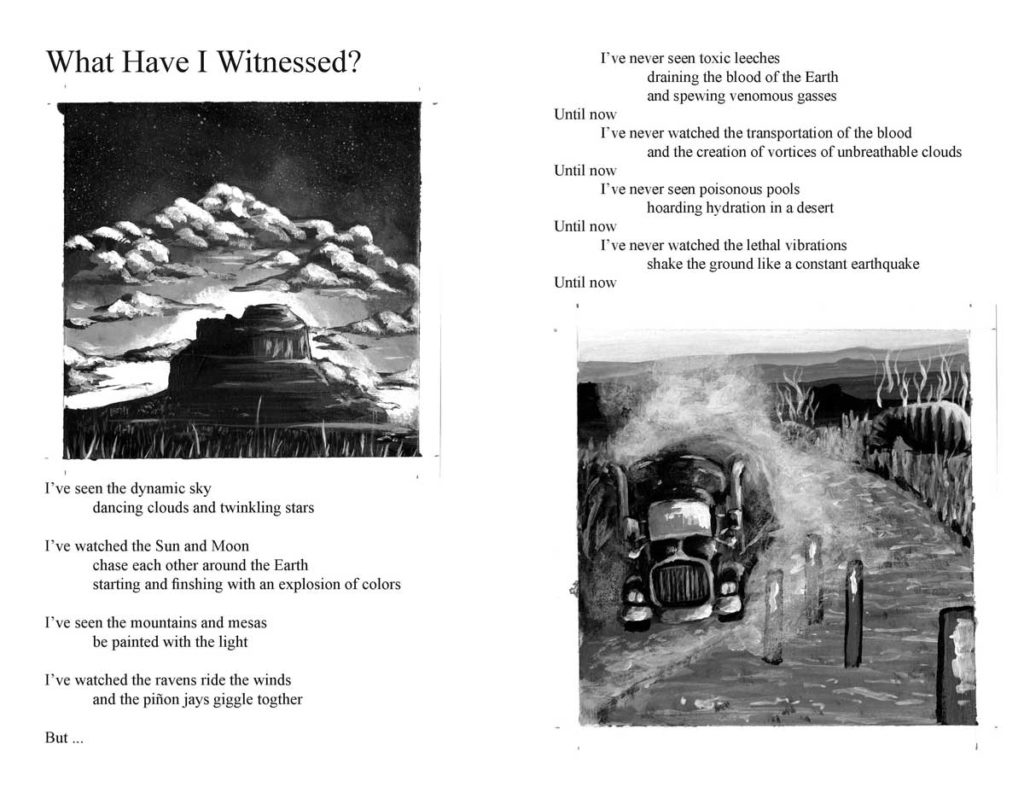

The artists involved in this project all take the position that the art zine Imbalance is art and self-expression. As art, it is “a creative manifestation and emotional expression of the artists’ experiences as witnessed in the Greater Chaco Region from meeting people, visiting Chaco Canyon, camping at Angel Peak BLM, going on the ‘Fracking is Fracking Reality Tour,’ discussing community health and environmental justice issues, and considering the welfare and care of all plants, animals, and beings who call this place home.” Unlike more traditional objects of art that are singular and remain “on view” in a museum context, this art zine is exhibited through its distribution process – through the process of the public interacting with it and taking a free copy home. The museum’s intention to distribute this art zine in conjunction with the exhibition Social & Sublime: Land, Place, Art is equal to exhibiting them as stationary and singular art objects. However, NMMoA and New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) delegitimized the art zines as mere distribution materials and excluded them from museum programming citing pseudo-legal and political reasons. We view this as censorship.

NMMoA and DCA initially censored the art zine, prohibiting it from being distributed through museum programming because it was too “political.” The Oxford English Dictionary definition of censorship is “the suppression or prohibition (exclusion) of any parts of books, films, news, etc. that are considered obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security.”

There appears to be an attempt by NMMoA and DCA to declare art zine collaborators who are active as Greater Chaco Coalition members as too “political” or as representing “private interest.” These collaborative zine partners live, work, and have deep cultural connections with the Greater Chaco Landscape. Politicizing their experiences, lives, spiritual beliefs, and health concerns as “private interest” is greatly troubling.

NMMoA never contacted the artists or collaborative partners to tell them that the art zine had been censored and would not be distributed. Instead, the artists found out they were missing from museum programming because two abandoned boxes of zines were found on top of a utility box on a residential street in Santa Fe and the artists were contacted by a resident who found them.

The artists contacted the NMMoA requesting information on the missing art zines and an update on how the zines were doing in the exhibition. No immediate response was given. One of the artists visited the museum to check and found that they were not in the exhibition. A brief email exchange ensued with museum staff and a cryptic letter was received citing Governmental Conduct Act at Section 10-16-3.1 NMSA 1978. It was at this point that the artists and collaborative partners issued a letter to NMMoA and DCA requesting information about what was happening.

Finally, four weeks later, NMMoA and DCA responded by lying to the artists and telling them that the context of the art zine distribution had changed and the art zines were no longer relevant to the exhibition. Also, they cited budget constraints which had affected programming. Therefore they were not included in “exhibition” museum programming for Social & Sublime: Land, Place and Art.

Emerging from this chaos of communications and events was a real desire to understand what happened. So on July 16, 2019, we the artists issued an Inspection of Public Records Act request for internal documents from NMMoA and DCA about the art zines. It is from these documents and our direct communications with museum staff that we have been able to piece together the facts on this issue. But we still wonder, what’s the whole story?

NMMoA and DCA chose not to tell the artists that the main reason for excluding the art zine and not distributing it was “for very good legal reasons” and that it was too “political.” Following concerns of censorship by the artists, the museum and DCA then quickly reinstated the zines back into museum programming and began distributing them through museum programming in the museum’s “resource center” in conjunction with a different exhibition, The Great Unknown: Artists at Glen Canyon and Lake Powell.

NMMoAand DCA additionally sought to limit the content of a related zine-making workshop by one of the artists; the IPRA documents contain internal communications stating “it would be ok for the project leader of the zines to teach a class on making zines, but not ok for the teacher to teach a class on how to make zines targeted at the political activity of opposing fracking.” The artist chose not to go through with this workshop, however, due to the censorship issue itself.

There are still remaining questions, not addressed in the IPRA documents. For instance, we do not see anywhere correspondence concerning the final decision to remove the art zine from museum programming. We are also baffled by the omission of language pertaining to fracking and the Government Conduct Act legal issue in the official NMMoA letter. This language appears in the draft letter to us, and then, suddenly disappears. We understand that internal meetings occurred, the content of which we’ll never be privy to. There is much left unanswered.

Taken as a whole, this troubling information has put us in a challenging situation. The situation goes far beyond any personal slight. Our professional responsibilities as artists in this community-engaged art zine project are many, and significant. We are responsible to the other artists who contributed to the project; we are responsible to our collaborative partners, representatives of Diné and Pueblo communities impacted directly by fracking activities; we are responsible to the native community groups who contributed financially to the printing of the zine so that indigenous voices living in impacted zones would be further amplified; and lastly, we are responsible to other artists–and museum workers–who look to address the issues of extraction in their work, and who may face–or may already have faced–prejudicial treatment in terms of what is permitted to be shown in state-sponsored institutions. This predetermined selectivity would appear to exist despite the fact that there is no outward/public statement about the museum’s stance on omitting work addressing fracking or other forms of extraction in state-sponsored museum programs. In this light, and for all these reasons, we feel it is our duty to reveal the truth of this censorship.

It gives us no joy to make this discovery, to assert that there was prejudicial treatment, and finally, to publicize it because we feel it is our moral imperative. In fact, we find it profoundly sad, and very distressing, that in a state in which impacted communities, mostly indigenous, are suffering real and documented health problems due to oil and gas development, that a state-sponsored institution would take steps to remove artwork which speaks to this crisis.

Quite simply, people are getting hurt in the sacrifice zones of Northern New Mexico – asthma rates are up, especially for children, as are cancer clusters, in the areas most heavily affected by oil and gas industry development. Hundreds of chemicals are released in fracking emissions, many of them known carcinogens, endocrine-disruptors, and respiratory irritants. For instance, at Lybrook Elementary School, in Counselor, NM a recent air test detected rates of hydrogen sulfide (a harmful chemical commonly emitted by gas wells) – at 7.6 µg/m3, well over three times what the U.S. EPA considers a reference concentration (quantitative metrics denoting appreciable risk to populations). Long-term exposure to the gas is associated with an elevated incidence of respiratory infections, irritation of the eyes and nose, cough, breathlessness, nausea, headache, and mental symptoms, including depression.

And simultaneously, in a time of unprecedented risks to climate, a cloud of methane the size of the state of Delaware–detected by NASA and confirmed to be directly related to fracking–hovers over the Four Corners area; methane is a greenhouse gas estimated at up to 100% more potent than carbon dioxide in trapping heat on the earth’s surface. In a state more at risk of water shortage than most in the U.S., the oil and gas industry is using millions of gallons of potable water, and is now pushing for the right to sell back New Mexico’s water–now fracked or “produced,” and laced with chemicals–back to us, New Mexico residents.

All the while, our state could be transitioning–even leading, nationally, in a just transition to renewables–with our abundant sun and wind, and also with our incredible capacity for community-building. We could be training New Mexico generations for renewable jobs, funneling renewable economy revenue streams into our schools and small businesses, and supporting the actual people of our state in meaningful ways while protecting our health, water, air, soil, food, and climate. Yet our state remains “captured” fiscally by an industry that claims we need them; with our education system ranked woefully low compared to other states in the country, and with children’s health actually suffering. We would hope that our cultural institutions would not be “captured” as well.

Agents of a state-sponsored cultural affairs department and museum are expected to reflect the many diverse voices of all of the people of this state–not to protect vested corporate interests. We believe it is wrong and harmful to silence the voices of indigenous and impacted communities because these state agencies assert they are overly “political.” We hope this does not continue to be the policy of the New Mexico Museum of Art and New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs; we urge them to reevaluate their stance.

As artists, we took on the creation of the Greater Chaco Art Zines to reflect and communicate the very real crisis we witnessed and to amplify the messages of community leaders who generously took time to meet with us and describe their experiences. Artists are meant to see, reflect, and express what is here, what is around us, and what is important. Stewards of cultural institutions have an obligation to nurture these relationships and processes and honor the truth-telling of our times–not silence them.