The museum blames misunderstanding, but zine artists say tribal perspectives on oil and gas were silenced.

By Elizabeth Miller March 31, 2020

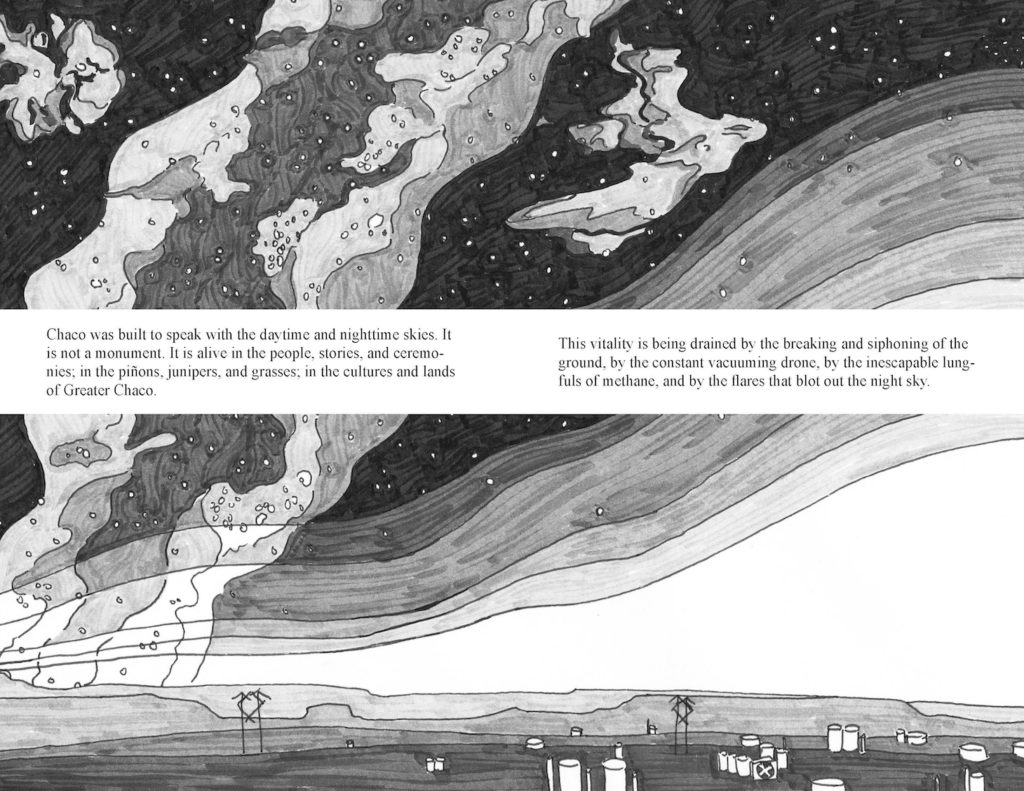

SANTA FE, New Mexico — Each year, Jeanette Hart-Mann takes her art students to northern New Mexico’s oil and gas fields. Not enough people understand what that development looks like, she insists, so she uses the University of New Mexico’s Land Arts of the American West program, which she is the director of, as a chance for students to experience it and create art in response. In 2018, Hart-Mann, her students, and guest artist Asha Canalos spent a week camping in the desert within sight of an oil and gas well. They met with indigenous community members upset by effects to their air, water, and quality of life, and toured the nearby UNESCO World Heritage site at Chaco Canyon, a place sacred to multiple tribes. Using paint, pencils, and solar-powered laptops and printers, they produced zines reflecting what they saw and heard.

“They were trying to make visible the invisible, and what happens? They get disappeared, too,” Hart-Mann told Hyperallergic.

A New Mexico Museum of Art curator requested copies of one of the zines to include in the exhibition Social and Sublime: Land, Place, and Art, but ultimately, the zine did not appear in the show. Museum staff attribute the change to reduced space and say regrettable misunderstandings arose around it. But Canalos and Hart-Mann say their work was removed from the state-funded museum’s exhibition for challenging an industry that dominates New Mexico’s economy. The National Coalition Against Censorship suggests the treatment infringed on their First Amendment rights and has encouraged the museum to reaffirm its commitment to artistic freedom.

Members of the Greater Chaco Coalition, a network of Native organizations and public lands advocates fighting fracking near Chaco Canyon, had shared their stories with the students and shown them around the landscape, and the organization was also helping to circulate the zines. The museum’s invitation was a welcome chance to reach a wider audience, Canalos told Hyperallergic. When most of the museum’s copies were returned to them without clear explanation, she and Hart-Mann filed an open records request for more information.

Emails that request produced included New Mexico’s Secretary of Cultural Affairs Debra Garcia y Griego (who did not respond to repeated interview requests), forwarding a response from legal counsel.

“All the poetry in the zine relates to what would unmistakenly [sic] be interpreted as political commentary on fracking,” the message reads. “If we distribute the zine it would be considered using state property to support the political cause of the Greater Chaco Coalition, something we are not authorized to do.”

Michelle Gallagher Roberts, the museum’s acting executive director, said their legal counsel misunderstood, thinking museum staff planned to hand zines to visitors, rather than make them available to pick up. They’d asked an attorney about the zines only because state funds were paying to print them, Roberts said. But Canalos and Hart-Mann said, and their emails show, they fundraised to cover printing costs.

Curators then cut space for Social and Sublime to extend a different exhibition, Roberts said. By the time the legal concerns were resolved, the zines no longer fit. Instead, they joined the education center for an exhibition on the Glen Canyon Dam, she said, which similarly dealt with political issues around land use.

“By that point, Jeanette and Asha, I think, were mistrustful because of our miscommunication, and we were really sorry about that miscommunication,” Roberts said. “There was never an attempt on our part to censor their point of view.”

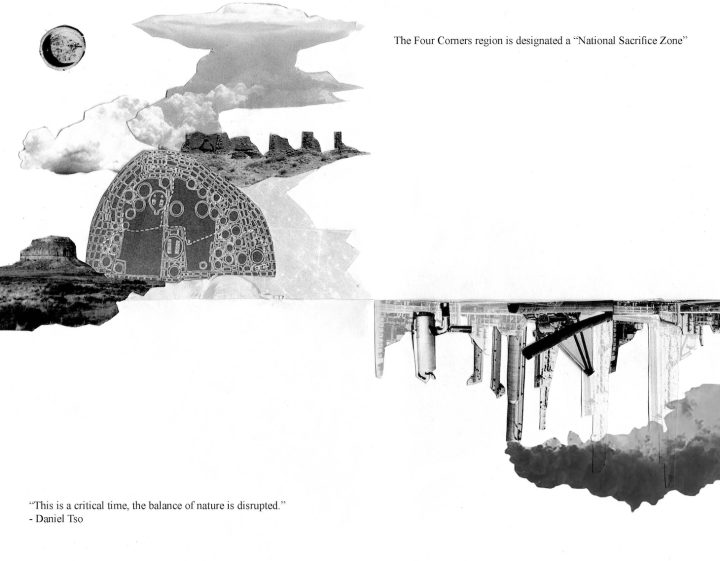

New Mexico ranks third in the nation for oil and gas production, and royalties from that industry provide roughly 40 percent of the state budget, including funding for the museum’s staff and building maintenance. A vast majority of those oil wells are hydraulically fractured, or fracked. Nothing in the public records shows issue-specific pressure, but Canalos remains convinced the industry influenced their treatment.

“This is state that has an incredible extraction history,” she said. “It’s clear that we’re kind of held hostage by that.”

On March 16, Svetlana Mintcheva, director of programs with the National Coalition Against Censorship, emailed Roberts and the Cultural Affairs Secretary. New Mexico’s financial dependence on the oil and gas industry may make condemnations of that industry controversial, she wrote. Still, she continued, “A publicly funded institution cannot discriminate against specific political positions, no matter how unpopular: such discrimination would violate the First Amendment.” She offered to help craft an inclusive mission statement, suggesting that as a good use of time with museums closed to avoid spreading coronavirus. Roberts declined.

Roberts said she has “never received official pushback” on controversial topics, adding, “We have always advanced a balanced perspective.”

Canalos and Hart-Mann are circulating a petition and posting updates on their website. Indigenous community members who collaborated on the zine, Canalos said, are “incensed.” Beata Tsosie Peña, a member of the Santa Clara Pueblo and Tewa Women United, a tribal women’s health nonprofit, said in a statement, “The museum needs to issue an apology and explicitly state in their policies that they do not discriminate or censor art for political content, especially when it is true artistic collaboration that reflects the societal issues of our time, and is lifting up the voices and perspectives of this place.”